I recently asked my favorite Elementary School teacher — Patty Hofer, my 3rd grade homeroom — what students REALLY need. I’m honored to publish her response below.

It was the start of a new school year in the 1980s, back when overhead projectors hummed and bulletin boards boasted cheerful slogans cut from construction paper. Teachers had survived the purgatory of prep week, those endless meetings that droned on about curriculum updates and emergency procedures. We smiled and nodded, but our minds were elsewhere—on the clutter of lesson plans and the crackle of new composition books waiting to be filled. The school gleamed, scrubbed to within an inch of its life, and the hallways smelled of textbooks and anticipation.

That first morning, on the front windows, classroom lists fluttered like little flags of hope. Parents and children crowded around, scanning for their names, their futures. Inside, I stood at my classroom door, greeting the children—my children—and their parents, offering a steady smile to calm their nerves. The bell rang, and the room filled with the chaotic joy of beginnings: the crackle of plastic wrap being torn from new crayons, the clatter of pencil boxes, and the tentative laughter of third graders sizing each other up. It was the smell of learning and the sound of potential.

I took record. Everyone was there—except Robert. His name lingered on the page like a shadow. I knew why. The news had been everywhere. Just days before, Robert’s little brother and a neighborhood friend had found a loaded gun, and they were playing with it. The gun fired, and that boy—just five years old, his backpack ready for his first day of kindergarten—was gone. Instead of school supplies, his family was picking out a casket.

A week or so later, Robert appeared. He slipped into the classroom without ceremony, like a boy trying not to wake a sleeping giant. He was smaller than I remembered, or maybe he just seemed that way. Robert had always been playful and full of mischief—the kind of child who made you want to laugh even as you told him to sit still. But now he was quieter, his light dimmed.

Because I was teaching in a church school, the Bible was part of our curriculum, and our Bible class was scheduled at 11:30 - 12:00 each day. As I was finishing the story of Jesus’ death – with Robert sitting in a desk close in front of me – I asked the class this question: “Have you ever done anything that was so awful that God couldn’t forgive you?”

The lunch bell rang, but the room was silent. Even with the promise of peanut butter sandwiches and pudding cups, no one stirred. And then, out of the stillness, Robert spoke. His voice was small but clear, like a stone dropped into a well.

“I have,” he said.

It wasn’t addressed to me, not really. It was more like he was speaking to the air, to the weight he carried. The other children froze. No one giggled or whispered. Even the clock seemed to stop ticking.

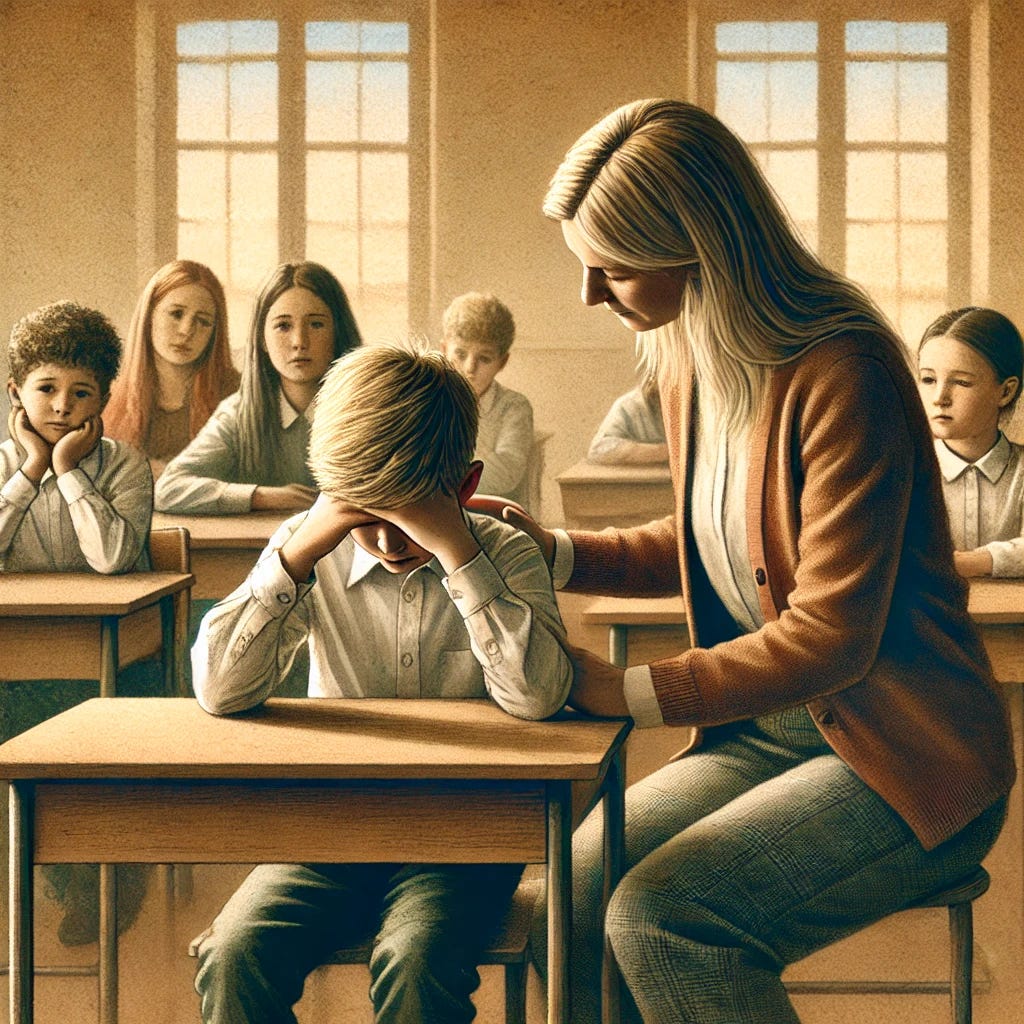

I knelt beside his desk. “Robert,” I asked gently, “what could you have done that’s so awful God couldn’t forgive you?”

He looked up at me, his eyes already brimming with tears. His voice cracked as he said, “I killed my little brother.”

I felt the air leave the room. The other children sat still, their peanut butter sandwiches forgotten. I reached for his hand, holding it lightly, as though it might break.

“How, Robert?” I asked softly. “How could you have done that?”

Through gasping sobs, he explained. His brother had been pestering him that morning to let him play with Robert and his friends. But Robert, feeling unwell and annoyed, had sent his little brother away. “NO!” he’d said. “Go find your own friends!” And off he went, leaving his little brother behind.

“If I’d let him come with us,” Robert said, his face crumpling, “he wouldn’t have been there. He wouldn’t have found the gun.”

It broke my heart to see a child carry so much pain. I thought of Peter, denying Jesus three times, and later grieving his death. The guilt must have been tremendous.

And then Jesus, risen from the dead, had called for Peter by name. “Go tell my disciples—and Peter,” He said. Not just the group, but specifically Peter: the one who denied Him. It was a reminder that even in our greatest failings, we are not abandoned.

I told Robert this story, how Jesus had forgiven Peter, how there was nothing—nothing—that could make God turn away from him.

The room was still as I spoke, the children hanging on every word. Robert’s sobs quieted, and his breathing slowed. We sat there for a while, long after the lunch bell had rung, the classroom wrapped in something that felt sacred.

Finally, Robert looked up at me. “Really?” he asked, his voice barely above a whisper.

“Really,” I said.

That day, I realized the sacred trust placed in a teacher’s hands. Children like Robert don’t need perfection or endless wisdom. They need us to notice their questions. Beneath every joke, every tear, every moment of mischief is a quiet request: “Will you see me? Will you care? Will God?” When we answer with presence instead of impatience, we give them the greatest gift we can offer—our humanity.

Children carry their own worlds with them, vast and unseen. In their laughter, their stories, and even their defiance, they ask us to help carry the weight of those worlds. Robert taught me that teaching is less about what we say and more about how we listen—because in the listening, we make their worlds just a little lighter.